Home (contents) → Miscellaneous → Tom Price’s flying machines

Tom Price’s flying machines

Tom Price’s trajectory in life and his outstanding contributions to hang gliding seem to be based on a solid foundation and to have also hinged upon a couple of remarkable changes of direction.

Beginnings

Initially Tom did poorly at school, then at age 16 he started airplane flying lessons at his father’s Air Force base flying club. His school grades subsequently went from Cs and Ds to As and Bs. He started at Embry Riddle Aeronautical Institute, Florida, in 1962, from where he graduated in 1965(5).

Tom then joined Douglas Aircraft in California. There he he worked as a structural engineer on Douglas DC-8, DC-9, and DC-10 airliners, using slide rules and mechanical calculators. He carried out analyses with pencil and paper, and for more complex analyses he used an old mainframe computer with punch card input.

He worked on the DC-10 from the start of the project to its first flight. At this time he also earned his commercial, instrument, and multi-engine airplane pilot ratings.

In a radical change of direction, which was uncannily fortuitous, also at this time he took up sailboat ocean racing.

In about 1970, during one of the largest aerospace down-turns to date, Tom was one of many laid off. He ‘went to the beach’ and continued crewing racing sailboats, which, unlike flying airplanes, he was able to do for free.

He joined Seal Beach loft where he learned the art of sailmaking. In 1972, an early hang glider sail came in for repair and two weeks later Tom was working for one of the early hang glider manufacturers: Eipper-Formance.

A couple of younger designers with high school educations were as good or better! They were brilliant and fearless! … I was 31, wiser, and more cautious, so my main contribution to the industry was more technical.

— Tom Price (12)

Albatross

A year later Tom set up his own business, Albatross Sails, initially making sails for other hang glider manufacturers. For example, see Donnita in Hang gliding 1975 part 2 for a photo of Donnita Holland flying her own design Rogallo hang glider in 1976 with a sail made by Albatross.

There Tom discovered something that others also found (including Miles Handley, struggling to manufacture his own advanced designs in Britain): The exactness required in hang glider sail construction exceeds that in boat sailmaking. The most practical method is to make both the frames and the sails together. Albatross Sails, where Tom partnered with top pilot Keith Nichols, then became a manufacturer of complete hang gliders. At one point, Tom teamed up with US Navy F-4 Phantom pilot and hang glider designer Rich Finley, who also has a masters degree in aeronautical engineering.(1)

At this time Tom Price even found time to assist Tom Peghiny of east coast manufacturer Sky Sports with his latest design. See Merlin in Flying squad, a short history of that manufacturer.

The ASG-21, in this picture being flown by Bettina Gray’s son Bill Liscomb, was an advanced hang glider by the standards of 1975.

Technical: Like the Sun IV (see under More developments in Hang gliding 1975 part 2) the tip struts of early ASG-21s were supported by short diagonal struts rather than by extensions of either the leading edge tubes or the tip tubes and attendant cables and attachments. On late versions even those struts were replaced by structure inside the sail. Notice also the method by which the airfoil section is defined at the root. Instead of a curved keel tube, the ASG-21 used a stand-up keel pocket. The first curved stand-up keel pocket I am aware of is that of the 1975 Skua, made in New Zealand. (See Skua in Graeme Bird’s hang gliders.)

See under External links later on this page for a color photo of an ASG-21 flying in Britain and for several video segments featuring Tom Price and his hang glider work.

ASG-23

The ASG-23 had struts instead of side wires and no top rigging or king post. The first such glider known to this author was Donnita Holland’s 1976 wing, the sail of which was made by Tom Price’s Albatross Sail Gliders. (See Donnita in Hang gliding 1975 part 2.) What made the ASG-23 unusual however, was that it had neither cross-tubes nor bowsprit, one of those structures normally considered necessary to prevent the airframe of a flex-wing from folding up as soon as any force is applied to it.

It used some carbon fiber, which also was not a new idea, the airframe of an experimental Ultralight Products Spyder having been constructed of carbon fiber in 1977, but the carbon Spyder did not see production.

The number of structural components are approximately one-third those of a conventional all aluminium frame yet the glider is designed to take aerobatic loads (especially negative loads).

— Dan Johnson (7)

Its leading edges were described by Dan Johnson as ‘semi-cantilevered’, which this author interprets to mean that bracing equivalent to cross-tubes was used, but up front near the nose. Incidentally, that new structural component was made of aluminium alloy, not carbon fiber. In addition, the leading edges ‘tapered as they neared the tip.'(13). While the side struts relieved that new structural component of some of the load conventionally borne (in compression) by cross-tubes, it must have been impressively strong even so.

The keel is pre-shaped and is totally faired into the root airfoil. The fixed tips are also internal.

–Dan Johnson (7)

One leading designer(9) regards the 1978 version of the ASG-23 as having inspired the overwhelmingly successful Ultralight Products Comet, which (as far as this author is aware) first flew in April 1979 with a partly carbon fiber airframe (dropped in favor of all aluminium). Dennis Pagen describes that early iteration of the ASG 23…

In 1978, Tom Price (currently chief engineer at Quicksilver microlights) designed the ASG 23 with bowed fiberglass cantilever leading edges (no kingpost). It too was pulled together with a winch. It handled well with weight-shift, but didn’t perform well due to all the wing twist (fiberglass is too flexible in this application).

— Dennis Pagen (10)

The photo of Larry Croome launching in the Canadian nationals in August 1980 is the first of the ASG-23 that this author has found (in his incomplete collection of magazines). Incidentally, Croome would have won the comp if he had not dropped the glider in a down-wind landing, which indicates the potential of this design. (8)

A later glider it resembled was Dick Boone’s ProAir Dawn. (See Bennett delta wing in Hang gliding mid 1980s.)

Incidentally, despite the ASG designation (for Albatross Sail Gliders, Tom Price’s company in California) its later incarnation pictured here was made by Canadian Ultralight Aircraft in Lumby, British Columbia, operated by Tom Price, Larry Croome, and Randy Rouck. (7)

Vehicle-based testing

By 1977, some hang gliders were nosing over and tumbling end-over-end because of insufficient pitch stability. They then tended to break because the airframes were not strong enough.

Being a designer/pilot, this was very scary stuff!

— Tom Price (12)

While Tom’s sound judgement prevented any of his gliders suffering from such problems, he felt it imperative to obtain real design data.

While sandbag testing of single surface gliders suspended upside-down is effective to test for structural strength, it cannot be used to test aerodynamic stability. In addition, with the advent of double surface wings that enclose the cross-tubes, sandbag testing for strength is not feasible. Tom Price was instrumental in setting up vehicle-based structural strength and aerodynamic stability testing of hang gliders in the U.S.A. That was shortly followed by similar efforts by hang gliding associations in other countries.

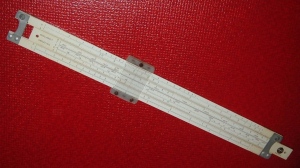

However, before the advent of vehicle-based testing, Tom advanced the state of the art of in-flight testing. He used an eight-millimetre movie film camera mounted on a cross-tube (of an ASG-21 it looks like) to record flight instrument data. Notice in the photo that the instruments are not in their normal position, but face outwards from the down-tube.

He also used a similar setup, but with the camera on the aft keel facing forward and the instruments mounted high on the control frame facing aft.

Author’s note: Notice also the dodgy hang loop and alloy non-locking karabiner, which were common at that time.

The instruments consisted of the following:

- Two airspeed indicators

- G meter

- Altimeter

- Clock

Notice also the mirror providing a view of the pilot’s motions and the glider’s angle relative to the horizon.

Incidentally, even the still camera was found to be useful in structural analysis as far back as 1973. See Steve McCarroll’s note on that subject in Trial and error in Hang gliding 1973 part 1.

The Electra Flyer Floater (described in the next section) with yarn tufts attached to the upper surface facilitated observation of airflow direction — particularly airflow reversal at the stall — both in flight and on a test vehicle. (In flight you can see the shadows of the tufts on the translucent sailcloth.)

Incidentally, every Wills Wing hang glider (as far as this author is aware) comes with a couple of tufts built into the sail to encourage pilots to study the airflow characteristics of their wings.

A safer method of testing was to use a vehicle. Initially, Tom tethered the glider to the top of the vehicle to carry out pitch stability tests manually.

Author’s note: Some British designers carried out similar ‘pitch feel’ tests on a hillside in a strong breeze. For example, see Dove in Hang gliding 1978 and 1979 part 2.

However, while such ‘pitch feel’ testing could determine that a glider was pitch stable in normal circumstances, it could not determine the degree to which that nose-up pitch force might resist the inertia of a severe nose-down pitching event caused either by pilot error or strong turbulence. (See under External links later on this page for film of Bob Keeler pitching over and breaking his wing.) Tom Price and a couple of friends set out to find those answers…

This method of attachment to the vehicle was also used to test for strength. However, this could do so only for positive G loads, which did not help with the pitch-over stability problem or with the strength of the airframe when subject to negative G.

Tom and his comrades then devised a four-pole attachment (a ‘quad pod’) that enabled testing of both positive and negative G — of both pitching moments and structural strength.

…if I had one award to give to the individual who singularly contributed the most to the development of hang gliders worldwide, I think it would be Tom Price. He invented and developed the hang glider test vehicle, and shared it with everyone.

— Wills Wing designer Steve Pearson (11)

Tom’s contributions to understanding longitudinal stability in hang gliders through the test vehicle and his analysis with Hewitt Phillips of NASA and Gary Valle of Sunbird Gliders facilitated aerodynamic advances in the years after 1977. (11)

For more about Gary Valle, see Back to the future in Hang gliding 1978 and 1979 part 2. For more about Hewitt Phillips, see under External links later on this page.

Forty-five years later, the only mechanism we have for evaluating longitudinal stability and structural integrity is the aerodynamic test vehicle.

— Steve Pearson (11)

See under External links also for Tom Price part-narrating film of structural testing on a dusty side road in the 1970s.

These efforts led to the formation of the Hang Glider Manufacturers Association and creation of airworthiness standards and testing procedures. Powered ultralights proved more problematic in this regard than did hang gliders and the FAA imposed regulations. Tom helped create the Light Sport Airplane airworthiness standards for the FAA.

Electra Floater

In early 1979 Tom Price, then working for Electra Flyer while its owner was away on a Transatlantic balloon adventure, was an early adopter of the removal of the drag-inducing and complex leading edge deflexors that had proliferated since the mid 1970s. Gary Valle of Sunbird claims to be the first with that innovation, in the Nova, but the Electra Flyer Floater, together with the slightly later Wills Wing Raven, was manufactured in far greater numbers. (See Back to the future in Hang gliding 1978 and 1979 part 2.) It was a design trend that all manufacturers quickly adopted, including Ultralight Products, whose Comet was about to further revolutionize hang glider design.

The Spirit was successor to the Floater.

Tom had previously developed the Cirrus 5 while at Electra Flyer, the popular successor to the Cirrus 3, the experimental Cirrus 4 never achieving production. (6)

Power

In 1981 or 1982 (or both) Tom worked for Wills Wing(2, 4). Then, in early 1983, he re-joined Eipper Aircraft, for whom he had worked in its days as one of the first three hang glider manufacturers in the world. This time he was in charge of powered ultralight development.(3)

See also Cronk works for earlier development of the Quicksilver hang glider from which the Quicksilver MX (powered ultralight with ‘multi-axis’ controls) in this photo was derived.

Related

Computing in hang gliding (related topics menu)

Douglas Aircraft: Coincidentally, Mike Markowski worked for the Douglas Aircraft company for a time, although I do not know whether he and Tom met. See Scientific American hang glider for more about Markowski.

Early powered ultralights part 2 for more of the powered Quicksilver

Eipper-Formance of Torrance, California (related topics menu)

Electra Flyer of Albuquerque, New Mexico (related topics menu)

Luff in the time of cholera: About the luffing dive

Sport Kites/Wills Wing of California (related topics menu)

Testing for stability and structural strength (related topics menu)

External links

Hang Gliding ASG20 Albatross Sails Hang Glider, a short film by Peter Brown on YouTube

ASG-21: Photo by Roger Middleton of Jerome Fack on an ASG21 at Pandy, Wales, in February 1977

Bob Keeler of Seagull Aircraft pitching over and breaking his wing in 1976: Big Blue Sky – The history of modern hang gliding – the first extreme sport! by Bill Liscomb, 2008, on YouTube starting at 59 minutes 24 seconds. Narration by Tom Peghiny (followed by part of the Bill Roecker interview).

Hewitt Phillips in NASA Hall of Honor

Tom Price interview in Big Blue Sky by Bill Liscomb on YouTube starting at 48 minutes 41 seconds. (Tom’s interview is followed by the voice of Chris Wills.)

Tom Price part-narrates structural testing on a dusty side road in Big Blue Sky starting at 1 hour, 3 minutes, 54 seconds. Bill Liscomb starts the narration, then Tom Price, followed by Tom Peghiny of east coast manufacturer Sky Sports, Bill Liscomb again, then the subject changes to the development of the emergency parachute.

References

1. W.A. Allen in Ground Skimmer, October 1974

2. Glider Rider, February 1980

3. Interview by Carol Price (Carol Boenish, who married Chris Price, no relation to Tom although both worked at Wills Wing at various times) Hang Gliding, March 1977

4. Glider Rider, March 1982

5. Whole Air, No. 28 January-February 1983

6. John LaTorre, who ran the Electra Flyer sail loft then the Flight Designs sail loft, writing in this post on the Hanggliding.org forum (October 2020)

7. ASG-23: Dan Johnson (presumably) Whole Air November 1980

8. Glider Rider, October 1980

9. One leading designer: Steve Pearson’s comment in Bob England, hang glider designer

10. ASG 23 with fiberglass leading edges in 1978: Dennis Pagen, SkyWings (BHPA magazine) May 1996, responding to an article about an experimental glider designed by Bill Brooks of Solar Wings

11. Author’s e-mail correspondence with Wills Wing designer Steve Pearson in August 2021

12. Fifty Years of Engineering, A Chronicle of an Embry Riddle Graduate’s Colorful Career, a presentation by Tom Price to Embry Riddle university, sent to the author in August 2021

13. ASG 23 by Ron Gleason on Oz Report Forum, 23 June 2007

Gusto en saludarlos.

Soy un admirador de las alas Delta y ultralight. Ver y escuchar (fotos, videos y literatura de aquella época, es algo Maravilloso, los cuales fueron ustedes los precursores de este hermoso mundo del vuelo.

Mucha historia como en el tiempo se ahido perfeccionando estas máquinas.

Tener una de estas alas Delta o ultralight de aquella época es fantástico.

Un gran abrazo a cada uno de ustedes que ya hicieron historia.

Atte.

H. Eduardo Osorio.

LikeLike

Google translation of Horacio’s message:

———————–

Nice to greet you.

I am a fan of delta wings and ultralight. Seeing and listening (photos, videos and literature of that time, is something Wonderful, which were you the forerunners of this beautiful world of flight.

Much history as in time I have perfected these machines.

Having one of these delta or ultralight wings from that era is fantastic.

A big hug to each of you who have already made history.

Atte.

H. Eduardo Osorio.

LikeLike

I just noticed a small error on this page, in the footnotes. I ran the sail loft at Electra Flyer first, from 1979 to 1980. I headed the sail loft at Flight Designs from 1980 to 1982. From 1982 to 1988, I ran the sail loft at Pacific Windcraft. I set up the sail loft for American Windwrights in 1988 but left shortly thereafter to go to Pacific Airwave. I headed the sail loft there for a year, and then turned it over to Jeff Williamson but stayed on as sailmaker making prototype sails and preparing them for production, until 1994.

LikeLike

Thanks John. I corrected the note (number 6). A bit late, but I only just noticed your comment. (The WordPress software usually notifies me of new comments, but I missed this somehow.)

LikeLike